Valentine’s Day is supposed to be about roses, chocolates, and that slightly unhinged belief that love conquers all. Ok, maybe I think it does.

But in 2016, the art world gave us a different kind of romance: a possessive, glitter-flecked, carbon-nanotube-coated love triangle between Surrey NanoSystems, Anish Kapoor, and Stuart Semple. It involved the blackest black ever made, the pinkest pink ever bottled, and a public middle finger that deserves its own place in art history.

Pull up a chair. This one’s juicy.

Chapter 1: The Seduction of the Void

Before the drama, there was science.

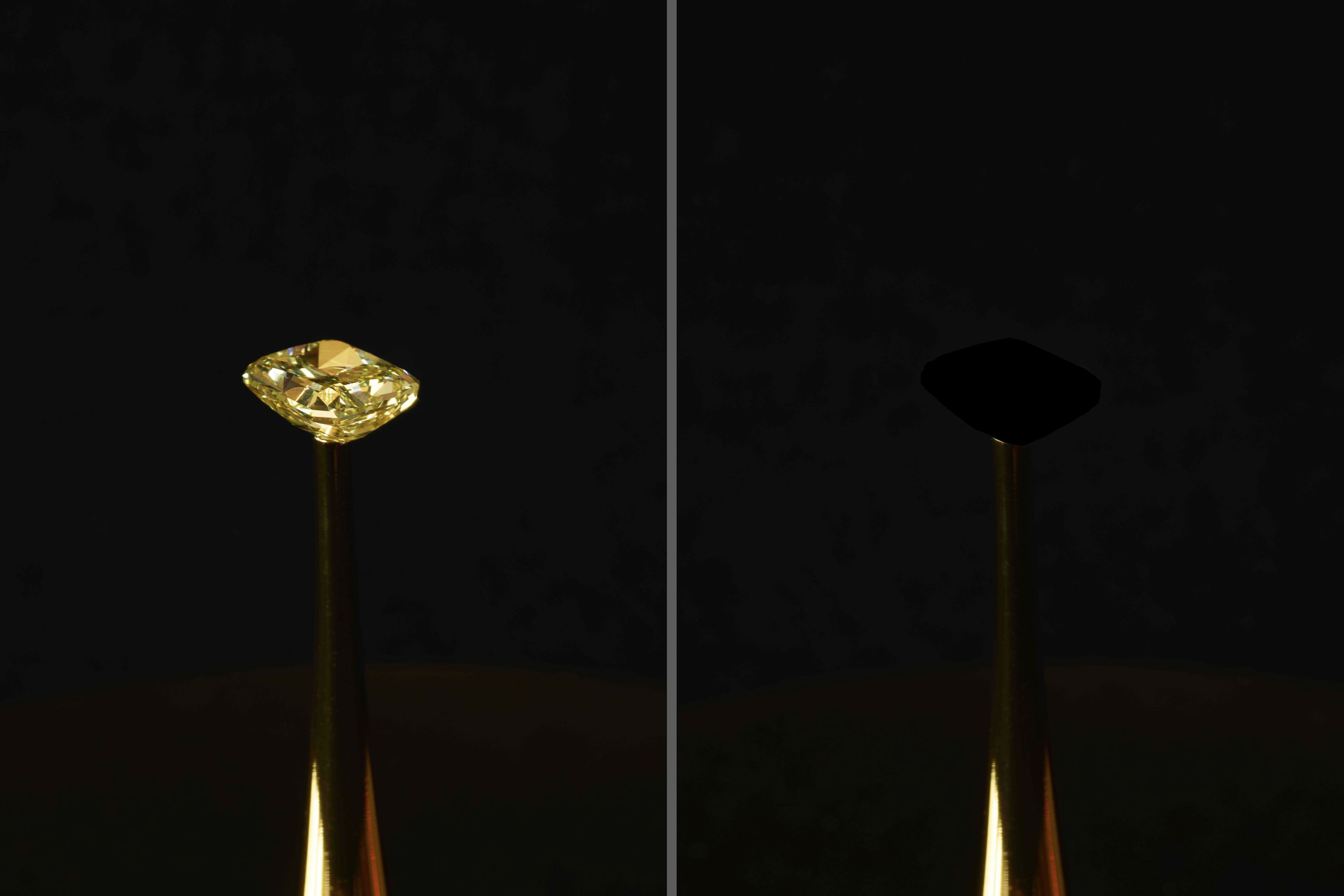

Vantablack—developed by Surrey NanoSystems—wasn’t just “a really dark paint.” It was a technological marvel made of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes: microscopic forests that trap light so efficiently it can absorb up to 99.9%+ of visible light. Instead of reflecting back to your eye, the light just… disappears. Objects coated in it look less like things and more like portals.

Originally, Vantablack was built for aerospace and optical systems—places where stray light is the enemy. But when images of this perception-bending material hit the public, artists collectively gasped. It wasn’t just black. It was the absence of form. The erasure of contour. The abyss in a jar.

And then came the twist.

In 2016, Anish Kapoor secured the exclusive rights to use Vantablack for artistic purposes.

Exclusive.

In a world where artists share studios, techniques, and solvents like communal wine bottles, this landed like someone whispering, “I’ve discovered the ultimate shade of black… and none of you can have it.”

Surrey NanoSystems, from a corporate perspective, likely saw this as a strategic licensing decision. From the art world’s perspective? It felt like Cupid had fired an arrow straight into the concept of artistic access and then locked the door behind him.

Chapter 2: Enter the Pink

If Vantablack was a brooding goth prince, Stuart Semple showed up in a neon tuxedo holding a glitter cannon.

Semple’s response was theatrical, mischievous, and—let’s be honest—brilliant. He released what he called “The World’s Pinkest Pink.” A fluorescent, retina-searing pigment so exuberant it practically hums.

And he made it available to everyone. Everyone… except Anish Kapoor!

To purchase it, buyers had to confirm they were not Kapoor, not affiliated with Kapoor, and not purchasing it on Kapoor’s behalf. It was part legal disclaimer, part performance art, part playground justice.

If Surrey NanoSystems had written a velvet-rope guest list, Semple built a technicolor block party.

Chapter 3: The Middle Finger Heard Round the Art World

Of course, this wasn’t going to end politely.

Kapoor somehow obtained the Pinkest Pink. Then he did what any restrained, contemplative sculptor might do in such a situation: he dipped his middle finger into the pigment and posted the image online.

Happy Valentine’s Day, everyone.

It was petty. It was glorious. It was peak 2016.

At this point, the colors themselves had become characters. Black was exclusivity, mystique, and controlled access. Pink was rebellion, access, and a wink to the crowd. The feud had officially become a live, global performance piece.

Just so you know what they look like, this is Stuart Semple and below is Anish Kapoor:

Chapter 4: The Arms Race of Absorption

Semple didn’t stop at pink. He launched BLACK 2.0. Then Black 3.0. Eventually Black 4.0—accessible, brushable paints that claimed to absorb staggering amounts of light (while still being, you know, usable by humans without a nanotechnology lab).

Meanwhile, Vantablack continued to exist in its rarefied realm—high-tech coatings, museum projects, and even that one-off BMW X6 covered in a Vantablack variant, looking like a stealth spaceship cosplaying as a car.

Surrey NanoSystems kept their crown jewel in carefully controlled contexts. Which, to be fair, makes sense for a specialized nanomaterial that isn’t exactly hardware-store friendly.

But culturally? They had already been cast as the slightly aloof gatekeeper of the abyss.

Chapter 5: What This Was Really About

Underneath the glitter and nanotubes, this wasn’t just a color fight.

It was about:

-

Who gets access to breakthrough materials

-

Whether color can—or should—be “owned”

-

The tension between corporate IP and artistic openness

-

And how easily art-world drama becomes art itself

Kapoor’s exclusivity deal was legal. Surrey NanoSystems’ strategy was corporate logic. Semple’s response was cheeky activism disguised as product launch.

But emotionally? It felt like someone said, “I love this color so much, I’m keeping it for myself,” and someone else replied, “Fine. I’ll invent a brighter one—and everyone’s invited.”

That’s Valentine’s energy if I’ve ever seen it.

Epilogue: So… Who Won?

Vantablack remains the technical champion of light absorption in specialized contexts. It’s still astonishing, still a marvel of engineering, still very much not something you casually paint your studio wall with.

The Pinkest Pink—and the cascade of open-access pigments that followed—became part of a broader cultural statement about accessibility and artistic community.

In the end, the real winner might have been the audience. We got a reminder that art isn’t just about finished objects. It’s about ego, access, rivalry, science, and sometimes a fluorescent pink middle finger dipped in pure defiance.

Which, frankly, feels like a love story for our time.

Now pass the chocolates.